- Home

- Brian Friel

Brian Friel Plays 1 Page 13

Brian Friel Plays 1 Read online

Page 13

SKINNER: ‘Through tattered clothes small vices do appear; Robes and furred gowns hide all.’

LILY: Mother of God, would you look at him! And the hat! What’s the rig, Skinner?

(SKINNER distributes the gowns.)

SKINNER: Mayor’s robes, alderman’s robes, councillor’s robes. Put them on and I’ll give you both the freedom of the city.

LILY: Skinner, you’re an eejit!

SKINNER: The ceremony begins in five minutes. The world’s press and television are already gathering outside. ‘Social upheaval in Derry. Three gutties become freemen.’ Apologies, Mr Hegarty! ‘Two gutties.’ What happened to the Orphans’Orchestra?

(He switches on the radio. A military band. They have to shout to be heard above it.)

MICHAEL: Catch yourself on, Skinner.

LILY: Lord, the weight of them! They’d cover my settee just lovely. (To MICHAEL) Put it on for the laugh, young fella.

SKINNER: Don the robes, ladies and gentlemen, and taste real power.

(LILY puts on her robe and head-dress. MICHAEL reluctantly puts on the robe only. SKINNER has the Union Jack in one hand and the ceremonial sword in the other.)

LILY: Lookat-lookat-lookat me, would you! (She dances around the parlour.) Di-do-do-da-di-doo-da-da.

(Sings) ‘She is the Lily of Laguna; she is my Lily and my –’. Mother of God, if the wanes could see me now!

SKINNER: Or the chairman.

LILY: Ooooops!

SKINNER: Lily, this day I confer on you the freedom of the City of Derry. God bless you, my child. And now, Mr Hegarty, I think we’ll make you a life peer. Arise Lord Michael – of Gas.

LILY: They make you feel great all the same. You feel you could – you could give benediction!

SKINNER: Make way – make way for the Lord and Lady Mayor of Derry Colmcille!

LILY: My shoes – my shoes! I can’t appear without my shoes! (MICHAEL takes off his robe and sits down. LILY joins SKINNER in a ceremonial parade before imaginary people. They both affect very grand accents. Very fast.)

SKINNER: How are you? Delighted you could come.

LILY: How do do.

SKINNER: My wife – Lady Elizabeth.

LILY: (Blows kiss) Wonderful people.

SKINNER: Nice of you to turn up.

LILY: My husband and I.

SKINNER: Carry on with the good work.

LILY: Thank you. Thank you.

SKINNER: Splendid job you’re doing.

LILY: We’re really enjoying ourselves.

(SKINNER lifts the flowers and hands them to LILY.)

SKINNER: From the residents of Tintown.

LILY: Oh, my! How sweet! (Stoops down to kiss a child.) Thank you, darling.

(SKINNER pauses below Sir Joshua. He is now the stern, practical man of affairs. The accent is dropped.)

SKINNER: This is the case I was telling you about, Sir Joshua. Eleven children in a two-roomed flat. No toilet, no running water.

LILY: Except what’s running down the walls. Haaaaa!

SKINNER: She believes she has a reasonable case for a corporation house.

LILY: It’s two houses I need!

SKINNER: Two?

LILY: Isn’t there thirteen of us? How do you fit thirteen into one house?

SKINNER: (To portrait) I know. I know. They can’t be satisfied.

LILY: Listen! Listen! I know that one! Do you know it, Skinner?

SKINNER: Elizabeth, please.

LILY: It’s a military two-step. The chairman was powerful at it. Give us your hand! Come on!

SKINNER: I think you’re concussed.

(She drags him into the middle of the parlour and sings as she dances. SKINNER sings with her.)

LILY: As I walk along the Bois de Boulogne with an independent air,

You can hear the girls declare, ‘He must be a millionaire’

You can hear them sigh and hope to die and can see them wink the other eye

At the man who broke the bank at Monte Carlo.

(LILY drops exhausted into a chair.)

O my God, I’m punctured!

SKINNER: Lovely, Lily. Lovely.

LILY: I wasn’t a bad dancer once.

SKINNER: And now Lord Michael will oblige with a

recitation – If – by the inimitable Rudyard Kipling. ‘If you can keep your head when all about you/Are losing theirs and blaming it on you …’ Ladies and gentlemen, a poem to fit the place and the occasion – Lord Michael of Gas!

(SKINNER switches off the radio and lights a cigar.)

MICHAEL: I don’t know what you think you’re up to. I don’t know what sort of a game you think this is. But I happen to be serious about this campaign. I marched three miles today and I attended a peaceful meeting today because every man’s entitled to justice and fair play and that’s what I’m campaigning for. But this – this – this fooling around, this swaggering about as if you owned the place, this isn’t my idea of dignified, peaceful protest.

SKINNER: (To LILY) I think he deserves to sign the Distinguished Visitors’ Book. Doesn’t he?

MICHAEL: You know what you’re campaigning for, Missus. You want a decent home. And you want a better life for your children than the life you had. But I don’t know what his game is. I don’t know what he wants.

SKINNER: Bunny Rabbit to romp home at twenties.

MICHAEL: Oh, as you say, he’s glib all right. But if you ask me he’s more at home with the hooligans, out throwing stones and burning shops!

(SKINNER pours himself a drink and sings quietly. Then very deliberately he stubs out his cigar on the leather-top desk.)

SKINNER: (Sings) Will you come into my parlour, said the spider to the fly.

’Tis the prettiest little parlour that ever you did spy.

MICHAEL: Look, Lily, look! I told you! I told you!

SKINNER: The way into my parlour is up a winding stair

And I have many curious things to show you when you’re there.

MICHAEL: He’s a vandal! He’s a bloody vandal!

(SKINNER pours a drink for LILY.)

SKINNER: Lily?

LILY: You’ll have me on my ear – God bless you. (To MICHAEL) Try that port wine, young fella. It’s gorgeous.

SKINNER: It’s sherry. Mr Hegarty?

(MICHAEL turns away and prepares to leave.)

SKINNER: Just the two of us, then, Lily. To … dignity.

MICHAEL: I’m going.

LILY: It’s time we were all leaving. They’ll be waiting for me to make the tea.

(SKINNER sits down and puts his feet up on the table.)

SKINNER: Would anyone object if I had another cigar?

(He lights one.)

LILY: What time is it anyway?

MICHAEL: Coming on to five.

LILY: D’you see my wanes? If I’m not there, not one of them would lift a finger. Three years ago last May the chairman won the five pound note in the Slate Club raffle and myself and Declan went on a bus run to Bundoran – I took him with me ’cos he doesn’t play about on the street with the others, you know – and when we come home at midnight, there they all were, with faces this length, sitting round the bare table, waiting since six o’clock for their tea to appear!

MICHAEL: I’m away, Lily. Good luck.

LILY: Good-bye, young fella. And keep at them books.

MICHAEL: (To SKINNER) Thanks for pulling me in.

SKINNER: My pleasure. And any time you’re this way, don’t pass the door.

LILY: And good luck on Easter Tuesday.

MICHAEL: Thanks. Thanks.

(Before MICHAEL reaches the door:)

SKINNER: Before you go, take a look out the window.

(MICHAEL stops, looks at SKINNER, then crosses to the window.)

SKINNER: Are they still there?

LILY: Is who still there?

SKINNER: The army. (To MICHAEL) Have they gone yet?

MICHAEL: The place is crawling with them. And there’s police there, too.<

br />

LILY: The army’s bad enough, but God forgive me I can’t stand them polis.

SKINNER: If I were you I’d wait till they move.

MICHAEL: Why should I?

SKINNER: Go ahead then.

MICHAEL: Why shouldn’t I?

SKINNER: Go ahead then.

MICHAEL: I’ve done nothing wrong.

SKINNER: How do you talk to a boy scout like that?

MICHAEL: I’ve done nothing I’m ashamed of.

SKINNER: You drank municipal whiskey. You masqueraded as a councillor. Theft and deception.

MICHAEL: All right, smart alec. (He tosses coins on the table.) That’s for the drink – there – there – there. Now give me one good reason why I can’t walk straight out of here and across that Square. One good reason – go on – go on.

SKINNER: Because you presumed, boy. Because this is theirs, boy, and your very presence here is a sacrilege.

MICHAEL: They don’t know we’re here.

SKINNER: They’ll see you coming out, won’t they?

MICHAEL: So they’ll see me coming out and they’ll arrest me for trespassing.

SKINNER: Have a brandy on me. They’ll soon shift.

MICHAEL: I certainly don’t want to be arrested. But if they want to arrest me for protesting peacefully – that’s all right – I’m prepared to be arrested.

SKINNER: They could do terrible things to you – break your arms, burn you with cigarettes, give you injections.

MICHAEL: Gandhi showed that violence done against peaceful protest helps your cause.

SKINNER: Or shoot you.

LILY: God forgive you, Skinner. There’s no luck in talk like that.

MICHAEL: As long as we don’t react violently, as long as we don’t allow ourselves to be provoked, ultimately we must win.

SKINNER: Do you understand Mr Hegarty’s theory, Lily?

LILY: Youse are both away above me.

MICHAEL: I told you my name’s Michael.

SKINNER: Mr Hegarty is of the belief that if five thousand of us are demonstrating peacefully and they come along and shoot us down, then automatically we … we … (To MICHAEL) Sorry, what’s the theory again?

MICHAEL: You know damn well the point I’m making and you know damn well it’s true.

SKINNER: It’s not, you know. But we’ll discuss it some other time. And as I said, if you’re passing this way, don’t let them entertain you in the outer office.

(MICHAEL goes back to the window and looks out. LILY giggles.)

LILY: D’you see our place? At this minute Mickey Teague, the milkman, is shouting up from the road, ‘I know you’re there, Lily Doherty. Come down and pay me for the six weeks you owe me.’ And the chairman’s sitting at the fire like a wee thin saint with his finger in his mouth and the comics up to his nose and hoping to God I’ll remember to bring him home five fags. And below us Celia Cunningham’s about half-full now and crying about the sweepstake ticket she bought and lost when she was fifteen. And above us Dickie Devine’s groping under the bed for his trombone and he doesn’t know yet that Annie pawned it on Wednesday for the wanes’ bus fares and he’s going to beat the tar out of her when she tells him. And down the passage aul Andy Boyle’s lying in bed because he has no coat. And I’m here in the Mayor’s parlour, dressed up like the Duchess of Kent and drinking port wine. I’ll tell you something, Skinner: it’s a very unfair world.

(The JUDGE appears on the battlements.)

JUDGE: One of the most serious issues for our consideration is the conflict between the testimony of the civilian witnesses and the testimony of the security forces on the vital question – Who fired first? Or to rephrase it – did the security forces initiate the shooting or did they merely reply to it? We have heard, for example, the evidence of Father Brosnan who attended the deceased and he insists that none of the three was armed. And I have no doubt that Father Brosnan told us the truth as he knew it. But I must point out that Father Brosnan was not present when the three emerged from the building. We have also the evidence of the photographs taken by Mr Montini, the journalist, and in none of these very lucid pictures can we see any sign whatever of weapons either in the hands of the deceased or adjacent to their person. But Mr Montini tells us he didn’t take the pictures until at least three minutes after the shooting had stopped. On the other hand we have the sworn testimony of eight soldiers and four policemen who claim not only to have seen these civilian firearms but to have been fired at by them. So at this point I wish to recall Dr Winbourne of the Army Forensic Department.

(WINBOURNE enters left. A Scotsman.)

WINBOURNE: My lord.

JUDGE: Dr Winbourne, in your earlier testimony you mentioned paraffin tests you carried out on the deceased. Could you explain in more detail what these tests involved?

WINBOURNE: Certainly, my lord. When a gun is fired, the propellant gases scatter minute particles of lead in two directions: through the muzzle and over a distance of thirty feet in front of the gun; and through the breach. In other words, if I fire a revolver or an automatic weapon or a bolt-action rifle (He illustrates with his own hand.) these lead particles will adhere to the back of this hand and between the thumb and forefinger. And a characteristic of this contamination is that there is an even-patterned distribution of these particles over the hand or clothing.

JUDGE: And the presence of this deposit is conclusive evidence of firing?

WINBOURNE: I’m a scientist, my lord. I don’t know what constitutes conclusive evidence.

JUDGE: What I mean is, if these lead particles are found on a person, does that mean that that person has fired a gun?

WINBOURNE: He may have, my lord. Or he may have been contaminated by being within thirty feet of someone who has fired in his direction. Or he may have been beside someone who has fired. Or he may have been touched or handled by someone who has just fired.

JUDGE: I see. And these distinctions are of the utmost importance because on this point we must be scrupulously meticulous. Thank you, Dr Winbourne, for explaining them so succinctly. So that, if we are to decide whether lead on a person’s hand or clothing should be attributed to his having fired a weapon, we must be guided by the pattern of deposit. Is that correct?

WINBOURNE: Yes, my lord.

JUDGE: And now, if I may return to your report – your findings on the three deceased.

WINBOURNE: In the case of Fitzgerald – it’s on page four, my lord.

JUDGE: I have it, thank you.

WINBOURNE: In the case of Fitzgerald, a smear on the left hand and on the left shirt sleeve. In the case of the woman Doherty, smear marks on the right cheek and shoulder. In the case of Hegarty an even deposit on the back of the left hand and between the thumb and forefinger.

JUDGE: A patterned deposit?

WINBOURNE: An even deposit, my lord.

JUDGE: So Hegarty certainly did fire a weapon?

WINBOURNE: Let me put it this way, my lord: I don’t see how he could have had these regular deposits unless he did.

JUDGE: And Fitzgerald and the woman Doherty?

WINBOURNE: They could have been smeared by Hegarty or they could have been contaminated while they were being carried away by the soldiers who shot them.

JUDGE: Or by firing themselves.

WINBOURNE: That’s possible.

JUDGE: But you are certain that Hegarty at least fired?

WINBOURNE: That’s what the tests indicate.

JUDGE: And you are personally convinced he did?

WINBOURNE: Yes, I think he did, my lord.

JUDGE: Thank you, Dr Winbourne.

(The JUDGE disappears, WINBOURNE goes off.)

MICHAEL: There’s three more tanks coming. And they seem to be putting up searchlights or something.

SKINNER: Are you asleep, Lily?

LILY: D’you know what I heard a man saying on the telly one night? D’you see them fellas that go up into outer space? Well, they don’t get old up there the way we get old down here. Whateve

r way the clocks work there, we age ten times as quick as they do.

SKINNER: You’re a real mine of information, Lily.

LILY: So that if I went up there and stayed up there long enough and then come down again, God I could end up the same age as Mark Antony!

SKINNER: No matter how long you’d stay up there, your family’d still be waiting for their tea.

LILY: I’d give anything to see the chairman’s face if that happened.

SKINNER: Lily.

LILY: What?

SKINNER: Why don’t you ring somebody?

LILY: Who?

SKINNER: Anybody.

LILY: That young fella’s out of his mind! Why in God’s name would I ring somebody?

SKINNER: To wish them a happy Christmas. To use the facilities of the hotel. Just for the hell of it. Anyone in the street got a phone?

LILY: Surely, We all have phones in every room. Haaaa!

SKINNER: Where do you get your groceries?

LILY: Billy Broderick.

SKINNER: Ring him.

LILY: Sure he’s across the road from me.

SKINNER: Tell him you’re out of tea.

LILY: Have you no head, young fella? He’d think I couldn’t face him just because I owe him fifteen pounds.

SKINNER: You must know someone with a phone.

LILY: Dr Sweeney!

SKINNER: No doubt. Anyone working in a shop – a factory?

LILY: No.

SKINNER: A garage – a café – an office – an –

LILY: Beejew Betty.

SKINNER: Who?

LILY: Betty Breen. She’s a cousin of the chairman. She’s in the cash desk of the Beejew Cinema. We call her Beejew Betty.

(SKINNER looks up the telephone directory. MICHAEL turns upstage.)

LILY: She used to let our wanes into the Saturday matinée for nothing. And then one Saturday our Tom – d’you see our Tom? Sixteen next October 23 and afeard of no man nor beast – he went up to her after the picture and told her it was the most stupidest picture he ever seen. And d’you know what? She took it personal. Niver let them in for free again. A real snob, Betty.

SKINNER: (Dials) 7479336.

LILY: What are you at? Sure I seen her last Sunday week at the granny’s.

(SKINNER hands her the phone.)

LILY: What will I say? What in the name of God will I say to –?

(Her accent and manner become suddenly stilted.)

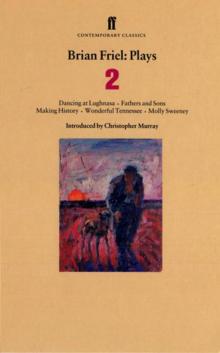

Brian Friel Plays 2

Brian Friel Plays 2 Brian Friel Plays 1

Brian Friel Plays 1