- Home

- Brian Friel

Brian Friel Plays 1

Brian Friel Plays 1 Read online

BRIAN FRIEL

Plays One

Philadelphia,

Here I Come!

The Freedom of the City,

Living Quarters,

Aristocrats,

Faith Healer,

and Translations

Introduced by

Seamus Deane

CONTENTS

Title Page

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Philadelphia, Here I Come!

Dedication

Characters

First Performance and Set

Episode One

Episode Two

Episode Three

Part I

Part II

The Freedom of the City

Dedication

Characters

First Performance and Set

Act One

Act Two

Living Quarters

Dedication

Characters

First Performance and Set

Act One

Act Two

Aristocrats

Dedication

Characters

First Performance and Set

Act One

Act Two

Act Three

Faith Healer

Dedication

Characters

First Performance and Set

Part One: Frank

Part Two: Grace

Part Three: Teddy

Part Four: Frank

Translations

Dedication

Characters

First Performance and Set

Act One

Act Two

Scene I

Scene II

Act Three

Greek and Latin Used in the Text

Select Checklist of Works

About the Author

By the Same Author

Copyright

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The publishers acknowledge with thanks the financial assistance of the Arts Council of Northern Ireland in the publication of this volume.

In The Freedom of the City, the song quotations ‘Lily of Laguna’, ‘Man who broke the bank’, ‘Where did you get that hat?’, reproduced by permission of Francis Day & Hunter Ltd.

In Aristocrats, lines quoted from the poem ‘My Father Dying’ from Weathering by Alastair Reid, Canongate, Edinburgh. ‘Sweet Alice’ by J. Kneass © 1933, Amsco Music Sales Co., New York City.

In Faith Healer, the song ‘The Way You Look Tonight’ from the film Swingtime with music by Jerome Kern, words by Dorothy Fields © 1936 T. B. Harms Co., British publishers Chappell Music Ltd. Reproduced by kind permission.

INTRODUCTION

Brian Friel was born into, and grew up in, the depressed and depressing atmosphere of the minority Catholic community in Northern Ireland. Derry, or, to give it its official name, Londonderry, had been, since the inception of the new Northern state as part of the United Kingdom in 1922, an economically depressed area. Male unemployment never sank below eighteen per cent, even during the artificial boom induced by the Second World War. Among the Catholic population, which was in the majority in the local electoral area, the rate was much higher. A corrupt electoral system also ensured that this local majority was deprived of power even within the limited field of borough politics. As a result, political tension remained high in the city during the decades of the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, even though it was paradoxically combined with a strange apathy which arose out of bad social conditions and a general feeling of desolation. These factors have profoundly impressed themselves on Friel’s writing in which the same blend of disappointment and unyielding pressure is found time and again to characterize the experience of his protagonists. There is another leavening element, however, which also takes its origin from the social and political circumstances of the place where he grew up. Derry is no more than a few miles from the political border which separates it from its natural hinterland, the county of Donegal, part of the Irish Free State, as it was then called. Friel spent his childhood and boyhood holidays in Donegal, where his family had originated. Famous for the beauty of its scenery, although no more fortunate in its economic condition, Donegal has remained for him as a powerful image of possibility, an almost pastoral place in which the principle of hope can find a source. The town of Ballybeg, which occurs so often in his plays as a standard setting, has fused within it the socially depressed and politically dislocated world of Derry and the haunting attraction of the lonely landscapes and traditional mores of rural Donegal.

Yet it would be wrong to emphasize these factors to the point of describing Friel’s work as being wholly political in its motivations and obsessions. Politics is an ever-present force, but Friel, conscious of the recurrent failures of the political imagination in Ireland, is concerned to discover some consolatory or counterbalancing agency which will offer an alternative. The discovery is never made. But the search for the alternative to and the reasons for failure brings Friel, finally, to the recognition of the peculiar role and function of art, especially the theatrical art, in a broken society. The moods of his plays and stories can change very rapidly from the farcical to the satirical to the sentimental to the tragic and at times the transition from one to another is disturbingly abrupt. The reason for this is that Friel has always found it necessary to struggle with the problem of temperament, an enhanced feature of people who are bedevilled by failure and compensate for it by making out of their own instability a mode of behaviour in which volatility becomes a virtue. Out of volatility, one can make a style; style can give off the effect of brilliance; but the brightness of the effect is very often in inverse ratio to the emptiness for which it is the consolation. This is not to say that Friel rehearses in his plays the conventional ‘Celtic’ temperament. But he does touch upon that convention, does even exploit it at times, but with the purpose of analysing the forces which produce it. Brilliance in the theatre has, for Irish dramatists, been linguistic. Formally, the Irish theatrical tradition has not been highly experimental. It depends almost exclusively on talk, on language left to itself to run through the whole spectrum of a series of personalities, often adapted by the same individual. Friel is unique, though, in his recognition that Irish temperament and Irish talk has a deep relationship to Irish desolation and the sense of failure. It is not surprising that his drama evolves, with increasing sureness, towards an analysis of the behaviour of language itself and, particularly, by the ways in which that behaviour, so ostensibly in the power of the individual, is fundamentally dictated by historical circumstances. His art, therefore, remains political to the degree that it becomes an art ensnared by, fascinated by its own linguistic medium. This is not obliquely political theatre. This is profoundly political, precisely because it is so totally committed to the major theatrical medium of words.

It is natural, given this, that Friel should make use of a conventional situation from the Irish theatrical tradition – that comic situation in which the dominant (but not necessarily heroic) figure on the stage is a social outsider or outcast who is nevertheless gifted with eloquence. The plight of such a figure always runs the risk of being sentimentalized, for it is an historical and political convention too, based on the experience of exile. From the beginning, in early plays like This Doubtful Paradise (1959) and The Enemy Within (1962), up to and including Philadelphia, Here I Come!, Friel has played a number of variations on the theme of exile. The central figures in these plays find themselves torn by the necessity of abandoning the Ireland which they love, even though, or perhaps because, they realize that they must bow to this necessity for the sake of their own integrity as individuals rather than as a consequence of economic or political pressures.

Although the different kinds of pressure forcing them to leave their homeland are interconnected, their ultimate perception is that fidelity to the native place is a lethal form of nostalgia, an emotion which must be overcome if they are, quite simply, to grow up. So Friel, in this first phase of his career, depicts a struggle already well known in other European literatures – the conflict between emotional loyalties to the backward and provincial area and obligations to the sense of self which seeks freedom in a more metropolitan, if shallower, world. The movement of historical forces has set against his provincial Donegal world and it has therefore become anachronistic. In feeling itself to be so, it also becomes susceptible to sentimentality, self-pity, and, in the last stages, to a grotesque caricaturing of what it had once been. For all that, it exercises a charm, a potent spell which the desire for freedom and for the future has tragic difficulty in breaking. In Philadelphia, Gar O’Donnell recites on several occasions the opening lines of Edmund Burke’s famous apostrophe to the ancien régime of France, written in 1790 by an Irishman who had made the preservation of ancestral feeling the basis for a counter-revolutionary politics and for a hostility to the shallow cosmopolitanism of the modern world. ‘It is now sixteen or seventeen years since I saw the Queen of France, then the Dauphiness, at Versailles; and surely never lighted on this orb, which she hardly seemed to touch, a more delightful vision …’ Friel uses Burke here, at some risk, to display the fact that the Ballybeg which Gar O’Donnell is trying to leave is indeed the remnant of a past civilization and that the new world, however vulgar it may seem, is that of Philadelphia and the Irish Americans. Although Gar is aware of the actual squalor of village life and of the coarseness of modern city life, his intelligence is of little consolation to him. To know the score is not a form of happiness. The most intolerable suspicion, however, is that, in leaving Ballybeg, he is forsaking the capacity to feel deeply. So he plays a game, cast in the form of a dialogue between his two selves, generating out of his own internal split a wonderful, comic and histrionic virtuosity which is nevertheless tinged throughout by grief. For this is a man who has been theatricalized by society, a man who must play the fool with his own feelings, thereby becoming the possessor of a temperament only because he has had no opportunity to stabilize into that achievement of a moral position which we call character. Gar O’Donnell is, in many ways, a recognizably modern case of alienation. He has all the narcissism that goes with the condition of being driven back in upon the resources of the self. But Friel is so specific in his evocation of the conditions of Irish life, so insistent in the deep-rooted sense of inherited failure, that the play has the freshness of a revelation rather than the routine characteristics of a well-known situation. Since the beginning of this century, Irish drama has been heavily populated by people for whom vagrancy and exile have become inescapable conditions about which they can do nothing but talk, endlessly and eloquently and usually to themselves. The tramps of Yeats and Synge and Beckett, the stationless slum dwellers of O’Casey or Behan, bear a striking family resemblance to Friel’s exiles.

After 1965, for six years. Friel’s career seemed to hesitate. Although his popularity with the Irish audience actually grew, and although that audience gratefully accepted plays like The Loves of Cass McGuire (1967), Lovers (1968), Crystal and Fox (1970), and the rather crude political satire, The Mundy Scheme (1970), there does seem, in retrospect, to have been an uncertainty in his writing which might account for its increasing sentimentality. Cass McGuire is an exile who returns home to harbour the illusion that the old people’s home she finds herself in is the real thing, rather than a junk yard for derelicts like herself. Although the play is brutal enough in its way, it hovers uneasily between satire and tragedy before finally settling for sentiment. In a similar manner, Fox Melarkey, the chief character in Crystal and Fox, destroys his masquerade of a showman’s life out of a frustration which we can sympathize with but which is offered to our understandings only as a glorified grumpiness that the world is not, after all, the Utopia he would like it to be. But in The Gentle Island (produced 1971, published 1973), Friel turned on all the illusions of pastoralism, ancestral feeling, and local piety that had been implicit in his dramatization of the world of Ballybeg. It is a savage play, ironically titled, executed in a destructive, even melodramatic spirit. The lives of the Sweeney family in the island of Inishkeen, off the west coast of County Donegal, are shown to be brutal, squalid, beset by sexual frustration and violence. A visitor is maimed, a whole tissue of illusions is swept aside, and a son finally escapes into the comparative freedom of the life of the Irish labourer in the Glasgow slums. The delicate tensions which had been so finely balanced in Philadelphia are now surrendered in an almost vengeful spirit. Lost illusions, and the sweetness of sexual love, are denied even a residual consolation. After this play, Friel had effectively cut himself off from his early work. He was seeking a new kind of drama, one in which the emotions of utter repudiation would replace the half-lights of exiled longing. The Mundy Scheme was a momentary attempt to turn towards political satire. But it was little more than a caricature play (although not, on that account, distant from the truth about the corruption of Irish political life). In a sense, up to 1971, Friel’s plays had been drawing a great deal of their power from the tenderness with which he had portrayed the decaying provincial world of Donegal – Derry in his short stories. Although he had early abandoned that form, he had not abandoned the attitudes which it had embodied. The plays gave more successful, subtler expression to those attitudes. But now, with the new, deeply angry sense of repudiation and disgust dominating his work, Friel moved on to the next phase of his writing career. From this point forward, his plays are more frankly ambitious, their form more flexible, their tone more resonantly that of drama which had reached a pitch of decisive intensity. All of Friel’s major work dates from the mid-1970s. Before that, he had been an immensely skilful writer who had found himself being silently exploited by the ease with which he could satisfy the taste for Irishness which institutions like the New Yorker and the Irish Theatre had become so expert in establishing. Although Philadelphia was a remarkable play, prefiguring some of the later work in its preoccupations, it was a virtuoso performance of the kind of Irish eloquence which had come to be expected from Irish playwrights in particular. It was ‘fine writing’. The horrifyingly stupefied condition of the Irish social and political world which it also revealed was treated almost as a foil to that brilliant chat of Gar O’Donnell. Friel had the courage to deprive himself of that ready-made appeal, that fixed audience, that commercial success, and to set out to write all over again the stories and plays of his immediate past.

He was stimulated to do so by the fact that the society he had known all his life began to break down, publicly and bloodily, in 1968. From the first marches of that year, in the summer and late autumn, to the murder of fourteen civilian marchers by British paratroopers in Derry in early 1972, Northern Ireland entered on the first phase of its long, slow disintegration. It was what everyone who knew the place had always expected; yet it was shocking when it came. Police and army, guerrillas and assassins, bombers and torturers became so prominent in a suddenly militarized society that the notion of its ever having been a decent unpolluted place seemed utterly absurd. The collapse of institutions and codes, the aridity of myths and slogans, all of which had seemed serenely potent only months before, had and still has profound repercussions for the people of that society. Friel had been there, imaginatively, before it happened. But the forces released by the breakdown inevitably had a transforming effect on him. Those first years of the ‘troubles’ saw him reject his own writing past; in those years he also began to confront what would dominate his writing in the future – the sense of a whole history of failure concentrated into a crisis over a doomed community or group.

Friel’s next four plays were produced in the Abbey Theatre before beginning their runs abroad in London and New York. After that, the pattern was broken and, although th

e Abbey will continue to produce his plays, it no longer has an assumed right to the first production. The plays, with dates of first performance, were The Freedom of the City (1973), Volunteers (1975), Living Quarters (1977) and Aristocrats (1979). In the first two of these, the political atmosphere is highly charged. The three central characters in Freedom are civil rights marchers trapped by the British Army in the mayor’s parlour of a city’s Guildhall. As they and others talk of their plight, it becomes clear that they will emerge only to be shot as terrorists. In Volunteers, the victimized group is a squad of IRA prisoners who have volunteered, against the orders of their own organization, to take temporary release from prison in order to help with an archaeological excavation. They know that, on their return to prison at the end of the dig, they will be murdered. Living Quarters and Aristocrats are studies in the breakdown of a family and its illusory social and cultural authority in the small-town setting of Ballybeg. All of these plays have in common an interest in the disintegration of traditional authority and in the exposure of the violence upon which it had rested. Despite the bleakness of the general situation, Friel manages to make his central victims appealing even in their futility and in their frequent bouts of self-pity. He still adheres to his fascination with the human capacity for producing consoling fictions to make life more tolerable. Although he destroys these fictions he does not, with that, destroy the motives that produced them – motives which are rooted in the human being’s wish for dignity as well as in his tendency to avoid reality.

In addition, these plays are full of what we may call displaced voices, American sociologists, English judges, and voice-overs from the past play their part in the dialogue in set speeches, tape-recordings, through loudspeakers. The discourse they produce is obviously bogus. Yet its official jargon represents something more and something worse than moral obtuseness. It also represents power, the one element lacking in the world of the victims where the language is so much more vivid and spontaneous. Once again, in divorcing power from eloquence, Friel is indicating a traditional feature of the Irish condition. The voice of power tells one kind of fiction – the lie. It has the purpose of preserving its own interests. The voice of powerlessness tells another kind of fiction – the illusion. It has the purpose of pretending that its own interests have been preserved. The contrast between the two becomes unavoidable at moments of crisis. Each of these plays presents us with such a moment, when both sets of voices are pitted against one another in a struggle which leads to a common ruin. Yet within the group of the victims there is another opposition which is perhaps more crucial and is certainly even more tense. It takes the form of a contrast too, between the fast-talking, utterly sceptical outsider and the silent, almost aphasic insider. At first, it seems to be a comic confrontation between a witty intelligence and a dumb stupidity. But it becomes tragic in the end and we are left to reflect that intelligence may be a gift, eloquence may be an attraction but that neither is necessarily a virtue and that the combination of both, in circumstances like these, may be disastrous. These outsiders are, dramatically speaking, dominating and memorable presences. Skinner in The Freedom of the City, Keeney in Volunteers, Ben in Living Quarters, Eamon in Aristocrats, are all men who make talk a compensation for their dislocation from family or society. They see clearly but, on that account, can do nothing. Against them, in the same plays, are ranged, respectively, Lily, Smiler, Ben in his second role of stammering nervousness and Casimir. Surrounding them are the voices of control – fathers, judges, narrators, expert analysts. Friel found in these plays a way to quarantine his central cast, with its tension between eloquence and silence, within a zone of official discourse with its ready-made jargon of inauthenticity. As a result, the plays are even more fiercely spoken plays. Language, in a variety of modes and presented in a number of recorded ways, dominates to the exclusion of almost everything else. The Babel of educated and uneducated voices, of speech flowing and speech blocked, the atmosphere of permanent crisis and of unshakable apathy, is as much a feature of Friel’s as it is of Beckett’s or of O’Casey’s plays.

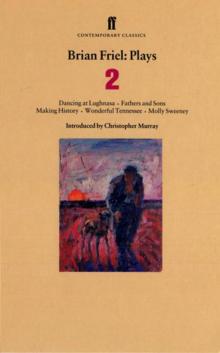

Brian Friel Plays 2

Brian Friel Plays 2 Brian Friel Plays 1

Brian Friel Plays 1